Anesthesia controls pain during surgery or other medical procedures. It includes using medicines, and sometimes close monitoring, to keep you comfortable. It can also help control breathing, blood pressure, blood flow, and heart rate and rhythm, when needed.

An anesthesiologist or a nurse anesthetist takes charge of your comfort and safety during surgery. This topic focuses on anesthesia care that you get from these specialists.Anesthesia may be used to:

- Relax you.

- Block pain.

- Make you sleepy or forgetful.

- Make you unconscious for your surgery.

What are the types of anesthesia?

- Local anesthesia numbs a small part of the body. You get a shot of local anesthetic directly into the surgical area to block pain. It is used only for minor procedures. You may stay awake during the procedure, or you may get medicine to help you relax or sleep.

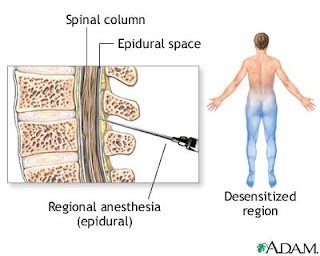

- Regional anesthesia blocks pain to a larger part of your body. Anesthetic is injected around major nerves or the spinal cord. You may get medicine to help you relax or sleep. Major types of regional anesthesia include:

- Peripheral nerve blocks. A nerve block is a shot of anesthetic near a specific nerve or group of nerves. It blocks pain in the part of the body supplied by the nerve. Nerve blocks are most often used for procedures on the hands, arms, feet, legs, or face.

- Epidural and spinal anesthesia. This is a shot of anesthetic near the spinal cord and the nerves that connect to it. It blocks pain from an entire region of the body, such as the belly, hips, or legs.

- General anesthesia affects the brain as well as the entire body. You may get it through a vein (intravenously), or you may breathe it in. With general anesthesia, you are completely unaware and do not feel pain during the surgery. General anesthesia also often causes you to forget the surgery and the time right after it.

What determines the type of anesthesia used?

The type of anesthesia used depends on several things:- Your past and current health. The doctor or nurse will consider other surgeries you have had and any health problems you have, such as heart disease, lung disease, or diabetes. You also will be asked whether you or any family members have had an allergic reaction to any anesthetics or medicines.

- The reason for your surgery and the type of surgery.

- The results of tests, such as blood tests or an electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG).

What are the potential risks and complications of anesthesia?

Major side effects and other problems of anesthesia are not common, especially in people who are in good health overall. But all anesthesia has some risk. Your specific risks depend on the type of anesthesia you get, your health, and how you respond to the medicines used.Some health problems increase your chances of problems from anesthesia. Your doctor or nurse will identify any health problems you have that could affect your care.

Your doctor or nurse will closely watch your vital signs, such as your blood pressure and heart rate, during anesthesia and surgery, so most side effects and problems can be avoided.

Preparing for Anesthesia

Being well-prepared for anesthesia may help you remain calm and relaxed. If you take the time to learn about your procedure and the anesthesia, you will be better able to understand the information and instructions you are given. Knowing what to expect can help decrease tension and anxiety.Usually, your surgeon's office, clinic, or hospital will contact you in advance to give you information about what to do the evening before and the day of the procedure. Your surgeon will also provide information about what will happen when you arrive at the clinic or hospital, during the procedure, and afterward.

Food and drink restrictions

As part of the preparation for your procedure, you are not allowed to eat or drink anything for a certain time period before anesthesia. The following times are averages. In some cases, such as in those people with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the restrictions must be started earlier for safety.- Do not eat for 6 hours before anesthesia.

- You may drink clear liquids only (water, filtered apple juice, black coffee or tea, and clear carbonated beverages such as Seven-Up) up to 2 hours before your surgery. You should having nothing else to eat or drink for at least 6 hours before anesthesia.

Medicine restrictions

If you take any medicines on a regular basis, such as diabetes medicines or heart medicines, ask your surgeon whether you should take your medicines on the day before or the day of your procedure. Some medicines may interact with the anesthetics and other medicines used for anesthesia.Informed consent

Before any nonemergency surgery or procedure, most surgery centers and hospitals have a surgery consent for you to sign. This is called an informed consent because your surgeon will explain why your surgery is needed, what it will involve, its risks and expected outcome, and how long it will take you to recover. After discussing this information, you may be asked to sign the informed consent. It needs to be signed before you receive any medicines that could affect your state of mind.Your anesthesia specialist will discuss the anesthesia care for your surgery so that you will understand what is involved, and you can then give your informed consent. You will be able to ask questions and express any concerns.

If the person undergoing anesthesia is a child or is mentally incompetent to sign a consent form, the consent may be signed by a responsible family member or guardian.

Mental relaxation techniques

Many people experience anxiety before medical procedures, especially surgery. Mental relaxation techniques can help reduce anxiety. If you will be awake during the procedure, you also can use these techniques to relax while it is being done. They can also be used to help reduce pain and anxiety following your procedure.Some mental relaxation techniques that may be useful include:

- Optimistic self-recitation, in which you focus on and recite thoughts that are optimistic and positive.

- Guided imagery (visualization), a method of using your imagination to help you relax and release tension by concentrating on a pleasant experience or restful scene.

- Meditation, to help focus your attention on feeling calm and relaxed. You may want to focus on a single image, a sound, or your own breathing.

- Distraction techniques, such as listening to music through headphones.

Medicine given before anesthesia

You may be given a medicine before anesthesia. Medicines may be given by mouth or by injection immediately before anesthesia.Medicine is given before anesthesia for many reasons, including:

- Relieve anxiety. The medicines most commonly given to relieve anxiety are benzodiazepines such as midazolam (Versed), diazepam (Valium), and lorazepam (Ativan).

- Relieve or prevent pain. Medicines to relieve pain (analgesics) may be given to people who are in pain before the procedure begins as well as to reduce pain during the procedure.

- Reduce secretions. Certain medicines (anticholinergic agents) may be used to reduce secretions in the mouth and respiratory tract.

- Reduce the volume and acidity of fluids in the stomach to help reduce the risk of aspiration. Aspiration occurs when an object or liquid is inhaled into the respiratory tract. In some cases, medicines are given to reduce or neutralize stomach acidity in order to lower the risk of injury if stomach juices are regurgitated into the throat or inhaled into the airway.

- Reduce nausea and vomiting. People who are at risk for nausea and vomiting either during the procedure or during recovery may receive medicines called antiemetics.

- Control body functions. Medicines may be given that help control the body's automatic responses to the pain and stress of surgery. Other medicines may be given to help maintain heartbeat or blood pressure at a stable and regular level.

Other preparation

For many procedures, medicines are given through a vein (intravenously, IV). An IV is usually inserted into a vein in the hand or lower arm. When the IV is in place, medicines or fluids can be given quickly into your bloodstream. Children and some adults may find insertion of the IV painful and stressful. In these cases, the IV may be inserted after they have been sedated or after an inhaled anesthetic has been given through a mask.Some of the instruments used to monitor your breathing, blood pressure, and heart function may be placed on your body while you are being prepared for your surgery.

Helping children prepare for anesthesia

Children do better when receiving anesthesia if they know what to expect. You can help relieve your child's anxiety or fears by being calm and explaining what will happen at the clinic or hospital. Explain to your child that he or she will be in unfamiliar surroundings but that many doctors and nurses will be there to help.It is best to be honest and explain that there may be some discomfort or pain after the procedure, but reassure your child that you will be close by. Bringing familiar items such as books or toys may help comfort and distract your child.

What happens when you are recovering from anesthesia?

Recovery from anesthesia occurs as the effects of the anesthetic medicines wear off and your body functions begin to return. Immediately after surgery, you will be taken to a post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), often called the recovery room, where nurses will care for and observe you. A nurse will check your vital signs and bandages and ask about your pain level.How quickly you recover from anesthesia depends on the type of anesthesia you received, your response to the anesthesia, and whether you received other medicines that may prolong your recovery. As you begin to awaken from general anesthesia, you may experience some confusion, disorientation, or difficulty thinking clearly. This is normal. It may take some time before the effects of the anesthesia are completely gone.

Your age and general health also may affect how quickly you recover. Younger people usually recover more quickly from the effects of anesthesia than older people. People with certain medical conditions may have difficulty clearing anesthetics from the body, which can delay recovery.

After anesthesia

Some of the effects of anesthesia may persist for many hours after the procedure. For example, you may have some numbness or reduced sensation in the part of your body that was anesthetized until the anesthetic wears off completely. Your muscle control and coordination may also be affected for many hours following your procedure. Other effects may include:- Pain. As the anesthesia wears off, you can expect to feel some pain and discomfort from your surgery. In some cases, additional doses of local or regional anesthesia are given to block pain during initial recovery. Pain following surgery can cause restlessness as well as increased heart rate and blood pressure. If you experience pain during your recovery, tell the nurse who is monitoring you so that your pain can be relieved.

- Nausea and vomiting. You may experience a dry mouth and/or nausea. Nausea and vomiting are common after any type of anesthesia. It is a common cause of an unplanned overnight hospital stay and delayed discharge. Vomiting may be a serious problem if it causes pain and stress or affects surgical incisions. Nausea and vomiting are more likely with general anesthesia and lengthy procedures, such as surgery on the abdomen, the middle ear, or the eyes. In most cases, nausea after anesthesia does not last long and can be treated with medicines called antiemetics.

- Low body temperature (hypothermia). You may feel cold and shiver when you are waking up. A mild drop in body temperature is common during general anesthesia because the anesthetic reduces your body's heat production and affects the way your body regulates its temperature. Special measures are often taken during surgery to keep a person’s body temperature from dropping too much (hypothermia).

In many cases minor surgical procedures are done on an outpatient basis, which means you will go home the same day. Before you are discharged from an outpatient clinic, you should be alert and able to understand and remember instructions. You will also want to make sure you have regained muscle control and coordination enough to walk safely, take fluids without vomiting, and take oral pain medicines safely. Depending on your medical history, your surgeon may also want you to be able to urinate before you are discharged.

When you are discharged, make sure you have:

- Reliable transportation to your home and for return to the hospital if complications develop. Do not plan to drive yourself home.

- A competent adult caregiver who can be with you for 24 hours after discharge.

- Access to a telephone so you can call for assistance if complications develop.

- Access to a pharmacy so you can obtain prescriptions.

Nurse anesthetist

A nurse anesthetist is a nurse who specializes in the administration of anesthesia.In the United States, a Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA) is an advanced practice registered nurse (APRN), a registered nurse (RN) who has acquired graduate-level education in anesthesia overseen by the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists's (AANA), Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs.

Training & Education

Nurse anesthetists must first complete a four-year bachelor's degree, usually a Bachelor of Science in Nursing but it can be a Bachelor of Science in another science-related subject in some instances. They must be a licensed registered nurse. In addition, candidates are required to have a minimum of one year of full-time nursing experience in an acute care setting, such as medical intensive care unit or surgical intensive care unit.[16] Following appropriate experience, applicants apply to a Council on Accreditation (COA) accredited program of anesthesia education for an additional 24 to 36 months, 6 to 9 contiguous semesters (only 2 out of the existing 107 programs are 2 years).[16] Realistically, it takes a CRNA 8 - 10 years of education, clinical training, and experience to attain this goal.Although all nurse anesthetists currently graduate with a master's degree, one may continue their education to the terminal degree level, either earning a Ph.D. or similar research doctorate (DNS, DNSc), or a clinical/practice doctorate such as a DNAP (Doctor of Nurse Anesthesia Practice), or DNP/DrNP (Doctor of Nursing Practice). At the terminal degree level, nurse anesthetists have available a wider variety of professional opportunities. They may teach, participate in administration, or pursue research. Currently, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing has endorsed a position statement that will move the current entry level of training for nurse anesthetists in the United States to the Doctor in Nursing Practice (DNP/DrNP) or Doctor of Nurse Anesthesia Practice (DNAP).[17] This move will affect all advance practice nurses, with a mandatory implementation by the year 2015.[18] The AANA announced in August 2007 support of this advanced clinical degree as an entry level for all nurse anesthetists, but with a target date of 2025. In accordance with traditional grandfathering rules, all those in current practice will not be affected.[17]

The didactic curricula of nurse anesthesia programs are governed by the Council on Acceditation (COA) standards and provide students the scientific, clinical, and professional foundation upon which to build sound and safe clinical practice. The basic nurse anesthesia academic curriculum and prerequisite courses focus on coursework in anesthesia practice: pharmacology of anesthetic agents and adjuvant drugs including concepts in chemistry and biochemistry (105 contact hours); anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology (135 contact hours); professional aspects of nurse anesthesia practice (45 contact hours); basic and advanced prinicples of anesthesia practice including physics, equipment, tehcnology and pain management (105 contact hours); research (30 contact hours); and clinical correlation conferences (45 contact hours).[16] Because all programs will be converting to a doctorate level education, the length of the programs, in most cases, will need to increase to 36 months (9 semesters) per the recommendation of the COA of Nurse Anesthesia Programs.[16]

Most programs exceed these minimum requirements. In addition, many require study in methods of scientific inquiry and statistics, as well as active participation in student-generated and faculty-sponsored research.[16]

Clinical residencies afford supervised experiences for students during which time they are able to learn anesthesia techniques, test theory, and apply knowledge to clinical problems. Students gain experience with patients of all ages who require medical, surgical, obstetrical, dental, and pediatric interventions. The results of a 1998 survey of program directors show that nurse anesthesia programs provide an average of 1,595 hours of clinical experience for each student.[16]Depending upon academic requirements, and all are at the master's degree level or higher.

The certification and recertification process is governed by the National Board on Certification and Recertification of Nurse Anesthetists (NBCRNA). CRNAs also have continuing education requirements and recertification every two years thereafter, plus any additional requirements of the state in which they practice.[16]

Compensation

In the United States, numerous salary reports throughout the years indicate that CRNAs remain the highest compensated of all nursing specialties as well as other non-physician healthcare providers. In 2009, the median annual salary for nurse anesthetists was $157,724 annually (not including call-pay, bonuses, pension, or benefits) as reported by the AMGA Medical Group Compensation and Financial Survey.Armed forces

In the United States armed forces, nurse anesthetists provide a critical peacetime and wartime skill. During peacetime and wartime, nurse anesthetists have been the principal providers of anesthesia services for active duty and retired service members and their dependents.[34] Nurse anesthetists function as the only licensed independent anesthesia practitioners at many military treatment facilities, including U.S. Navy ships at sea. They are also the leading provider of anesthesia for the Veterans Administration and Public Health Service medical facilities.During World War I, America's nurse anesthetists played a vital role in the care of combat troops in France. From 1914 to 1915, three years prior to America entering the war, Dr. George Crile and nurse anesthetists Agatha Hodgins and Mabel Littleton served in the Lakeside Unit at the American Ambulance at Neuilly-sur-Seine in France.[35][36] In addition, they helped train the French and British nurses and physicians in anesthesia care. After the war, France continued to use nurse anesthetists, however, Britain adopted a physician-only policy that continues today. In 1917, the American participation in the war resulted in the U.S. military training nurse anesthetists for service. The Army and Navy sent nurses to various hospitals, including the Mayo Clinic at Rochester and the Lakeside Hospital in Cleveland, for anesthesia training, before overseas service.[37]

Among notable nurse anesthetists are Sophie Gran Winton, who served with the Red Cross at an army hospital in Château-Thierry, France, and earned the French Croix de Guerre in addition to other service awards;[38] Anne Penland, who was the first nurse anesthetist to serve on the British Front and was decorated by the British government and [39]

American nurse anesthetists also served in World War II and Korea, receiving numerous citations and awards.[40] Second Lieutenant Mildred Irene Clark provided anesthesia for casualties from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.[41] During the Vietnam War, nurse anesthetists served as both CRNAs and flight nurses, and also developed new field equipment.[42] Nurse anesthetists have been casualties of war. Lieutenants Kenneth R. Shoemaker, Jr. and Jerome E. Olmsted, were killed in an air evac mission in route to Qui Nhon, Vietnam.[43]

At least one nurse anesthetist was a prisoner of war; Army nurse anesthetist Annie Mealer endured a three-year imprisonment by the Japanese in the Philippines, and was released in 1945.[44] During the Iraq War, nurse anesthetists comprise the largest group of anesthesia providers at forward positioned medical treatment facilities.[45] In addition, they play a role in the continuing education and training of Department of Defense nurses and technicians in the care of wartime trauma patients.

No comments:

Post a Comment