Definition

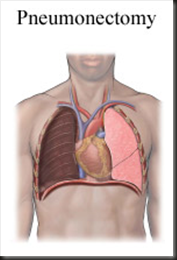

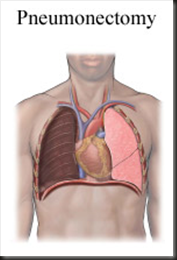

Pneumonectomy is the medical term for the surgical removal of a lung.

Purpose

A pneumonectomy is most often used to treat lung cancer when less radical surgery cannot achieve satisfactory results. It may also be the most appropriate treatment for a tumor located near the center of the lung that affects the pulmonary artery or veins, which transport blood between the heart and lungs. In addition, pneumonectomy may be the treatment of choice when the patient has a traumatic chest injury that has damaged the main air passage (bronchus) or the lung's major blood vessels so severely that they cannot be repaired.

Demographics

Pneumonectomies are usually performed on patients with lung cancer, as well as patients with such noncancerous diseases as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis. These diseases cause airway obstruction.

Approximately 361,000 Americans die of lung disease every year. Lung disease is responsible for one in seven deaths in the United States, according to the American Lung Association. More than 25 million Americans are now living with chronic lung disease.

Lung cancer

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. It is expected to claim nearly 157,200 lives in 2003. Lung cancer kills more people than cancers of the breast, prostate, colon, and pancreas combined. Cigarette smoking accounts for nearly 90% of cases of lung cancer in the United States.

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer among both men and women and is the leading cause of death from cancer in both sexes. In addition to the use of tobacco as a major cause of lung cancer among smokers, second-hand smoke contributes to the development of lung cancer among nonsmokers. Exposure to asbestos and other hazardous substances is also known to cause lung cancer. Air pollution is also a probable cause, but makes a relatively small contribution to incidence and mortality rates. Indoor exposure to radon may also make a small contribution to the total incidence of lung cancer in certain geographic areas of the United States.

In each of the major racial/ethnic groups in the United States, the rates of lung cancer among men are about two to three times greater than the rates among women. Among men, age-adjusted lung cancer incidence rates (per 100,000) range from a low of about 14 among Native Americans to a high of 117 among African Americans, an eight-fold difference. For women, the rates range from approximately 15 per 100,000 among Japanese Americans to nearly 51 among Native Alaskans, only a three-fold difference.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The following are risk factors for COPD:

- current smoking or a long-term history of heavy smoking

- employment that requires working around dust and irritating fumes

- long-term exposure to second-hand smoke at home or in the workplace

- a productive cough (with phlegm or sputum) most of the time

- shortness of breath during vigorous activity

- shortness of breath that grows worse even at lower levels of activity

- a family history of early COPD (before age 45)

Diagnosis/Preparation

Diagnosis

In some cases, the diagnosis of a lung disorder is made when the patient consults a physician about chest pains or other symptoms. The symptoms of lung cancer vary somewhat according to the location of the tumor; they may include persistent coughing, coughing up blood, wheezing, fever, and weight loss. In cases involving direct trauma to the lung, the decision to perform a pneumonectomy may be made in the emergency room. Before scheduling a pneumonectomy, however, the surgeon reviews the patient's medical and surgical history and orders a number of tests to determine how successful the surgery is likely to be.

In the case of lung cancer, blood tests, a bone scan, and computed tomography scans of the head and abdomen indicate whether the cancer has spread beyond the lungs. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is also used to help stage the disease. Cardiac screening indicates how well the patient's heart will tolerate the procedure, and extensive pulmonary testing (e.g., breathing tests and quantitative ventilation/perfusion scans) predicts whether the remaining lung will be able to make up for the patient's diminished ability to breathe.

Preparation

A patient who smokes must stop as soon as a lung disease is diagnosed. Patients should not take aspirin or ibuprofen for seven to 10 days before surgery. Patients should also consult their physician about discontinuing any blood-thinning medications such as coumadin or warfarin. The night before surgery, patients should not eat or drink anything after midnight.

Description

In a conventional pneumonectomy, the surgeon removes only the diseased lung itself. The patient is given general anesthesia. An intravenous line inserted into one arm supplies fluids and medication throughout the operation, which usually lasts one to three hours.

The surgeon begins the operation by cutting a large opening on the same side of the chest as the diseased lung. This posterolateral thoracotomy incision extends from a point below the shoulder blade around the side of the patient's body along the curvature of the ribs at the front of the chest. Sometimes the surgeon removes part of the fifth rib in order to have a clearer view of the lung and greater ease in removing the diseased organ.

A surgeon performing a traditional pneumonectomy then:

- deflates (collapses) the diseased lung

- ties off the lung's major blood vessels to prevent bleeding into the chest cavity

- clamps the main bronchus to prevent fluid from entering the air passage

- cuts through the bronchus

- removes the lung

- staples or sutures the end of the bronchus that has been cut

- makes sure that air is not escaping from the bronchus

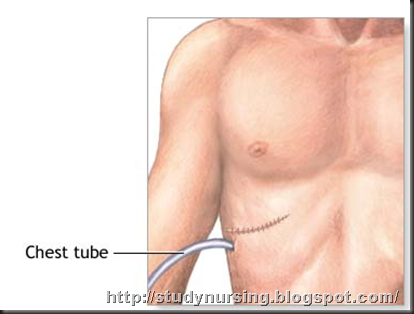

- inserts a temporary drainage tube between the layers of the pleura (pleural space) to draw air, fluid, and blood out of the surgical cavity

- closes the chest incision

Nursing Management

As part of preparing for a pneumonectomy, your healthcare provider should give you specific instructions, telling you where and when to arrive at the medical facility, how to prepare yourself, and what to expect the day of and the days following your procedure.

Make sure to bring a list of the medicines you take right now, including:

- Prescriptions from your doctor

- Over-the-counter medications

- Supplements, like vitamins or herbal remedies.

Make a note of what time and how much of each medicine you take. Also tell your healthcare provider if you have any allergies. This is important for every visit with your doctor and any time you need to go to the hospital.

You might need to stop taking some kinds of medicine before the pneumonectomy. If you smoke, you need to stop smoking before the surgery. You will also be asked to not eat or drink anything for at least eight hours before your operation.

A pneumonectomy is done in the hospital. Following the surgery, most people need to stay in the hospital for about five to seven days. Some people need to stay longer. You may want to have someone drive you to the hospital and help you get settled in. Also, most people need someone to drive them home when leaving the hospital.

Chest tubes drain fluid from the incision and a respirator helps the patient breathe for at least 24 hours after the operation. The patient may be fed and medicated intravenously. If no complications arise, the patient is transferred from the surgical intensive care unit to a regular hospital room within one to two days.

After care

A patient who has had a conventional pneumonectomy will usually leave the hospital within 10 days. Aftercare during hospitalization is focused on:

- relieving pain

- monitoring the patient's blood oxygen levels

- encouraging the patient to walk in order to prevent formation of blood clots

- encouraging the patient to cough productively in order to clear accumulated lung secretions

If the patient cannot cough productively, the doctor uses a flexible tube (bronchoscope) to remove the lung secretions and fluids.

Recovery is usually a slow process, with the remaining lung gradually taking on the work of the lung that has been removed. The patient may gradually resume normal non-strenuous activities. A pneumonectomy patient who does not experience postoperative problems may be well enough within eight weeks to return to a job that is not physically demanding; however, 60% of all pneumonectomy patients continue to struggle with shortness of breath six months after having surgery.

Risks

The risks for any surgical procedure requiring anesthesia include reactions to the medications and breathing problems. The risks for any surgical procedure include bleeding and infection.

Between 40% and 60% of pneumonectomy patients experience such short-term postoperative difficulties as:

- prolonged need for a mechanical respirator

- abnormal heart rhythm (cardiac arrhythmia); heart attack (myocardial infarction); or other heart problem

- pneumonia

- infection at the site of the incision

- a blood clot in the remaining lung (pulmonary embolism)

- an abnormal connection between the stump of the cut bronchus and the pleural space due to a leak in the stump (bronchopleural fistula)

- accumulation of pus in the pleural space (empyema)

- kidney or other organ failure

Over time, the remaining organs in the patient's chest may move into the space left by the surgery. This condition is called postpneumonectomy syndrome; the surgeon can correct it by inserting a fluid-filled prosthesis into the space formerly occupied by the diseased lung.

Normal results

The doctor will probably advise the patient to refrain from strenuous activities for a few weeks after the operation. The patient's rib cage will remain sore for some time.

A patient whose lungs have been weakened by noncancerous diseases like emphysema or chronic bronchitis may experience long-term shortness of breath as a result of this surgery. On the other hand, a patient who develops a fever, chest pain, persistent cough, or shortness of breath, or whose incision bleeds or becomes inflamed, should notify his or her doctor immediately.

Morbidity and mortality rates

In the United States, the immediate survival rate from surgery for patients who have had the left lung removed is between 96% and 98%. Due to the greater risk of complications involving the stump of the cut bronchus in the right lung, between 88% and 90% of patients survive removal of this organ. Following lung volume reduction surgery, most investigators now report mortality rates of 5–9%.

Alternatives

Lung cancer

The treatment options for lung cancer are surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, either alone or in combination, depending on the stage of the cancer.

After the cancer is found and staged, the cancer care team discusses the treatment options with the patient. In choosing a treatment plan, the most significant factors to consider are the type of lung cancer (small cell or non-small cell) and the stage of the cancer. It is very important that the doctor order all the tests needed to determine the stage of the cancer. Other factors to consider include the patient's overall physical health; the likely side effects of the treatment; and the probability of curing the disease, extending the patient's life, or relieving his or her symptoms.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Although surgery is rarely used to treat COPD, it may be considered for people who have severe symptoms that have not improved with medication therapy. A significant number of patients with advanced COPD face a miserable existence and are at high risk of death, despite advances in medical technology. This group includes patients who remain symptomatic despite the following:

- smoking cessation

- use of inhaled bronchodilators

- treatment with antibiotics for acute bacterial infections, and inhaled or oral corticosteroids

- use of supplemental oxygen with rest or exertion

- pulmonary rehabilitation

After the severity of the patient's airflow obstruction has been evaluated, and the foregoing interventions implemented, a pulmonary disease specialist should examine him or her, with consideration given to surgical treatment.

Surgical options for treating COPD include laser therapy or the following procedures:

- Bullectomy. This procedure removes the part of the lung that has been damaged by the formation of large air-filled sacs called bullae.

- Lung volume reduction surgery. In this procedure, the surgeon removes a portion of one or both lungs, making room for the remaining lung tissue to work more efficiently. Its use is considered experimental, although it has been used in selected patients with severe emphysema.

- Lung transplant. In this procedure a healthy lung from a donor who has recently died is given to a person with COPD.

Purpose

Purpose