Hypothermia is defined as a core, or internal, body temperature of less than 95°F (35°C). The tragic tales of people falling into icy lakes are poignant examples of hypothermia. Anyone exposed to cold temperatures, whether for work or recreation, may be at risk of becoming too cold.

Hypothermia has been a military problem ever since Hannibal lost nearly half of his troops while crossing the Pyrenees Alps in 218 B.C. and has continued to plague military campaigns through both world wars and the Korean War.

Today, with the popularity of an expanding number of winter sports and increasing at-risk populations, hypothermia has slowly become a civilian, urban problem.

Sometimes the body’s temperature control can be altered by disease. In this case, core body temperature can decrease in almost any environment. This condition is called secondary hypothermia.

Any person who is at risk for hypothermia and is suspected to have sustained a cold exposure should be brought to a hospital’s Emergency Department. Look for these danger signs of cold exposure:

Those whose core temperatures are below 89.9°F (32.2°C) are admitted to the hospital. Underlying medical disorders are investigated and cardiac monitoring performed.

People with uncomplicated hypothermia do better as a group than do people with hypothermia and another associated disease. In fact, outcome depends more on the underlying disease process than the person’s initial temperature or the rewarming method employed.

Age is not always a risk factor, although elderly people tend to have more associated medical problems. People with mild to moderate hypothermia usually have a complete recovery.

People with poor outcomes usually have had cardiac arrest, a very low or no blood pressure, and the need to have breathing assisted with a tube—all before arriving at the hospital.

Hypothermia has been a military problem ever since Hannibal lost nearly half of his troops while crossing the Pyrenees Alps in 218 B.C. and has continued to plague military campaigns through both world wars and the Korean War.

Today, with the popularity of an expanding number of winter sports and increasing at-risk populations, hypothermia has slowly become a civilian, urban problem.

Hypothermia Causes

Normal body temperature is the reflection of a delicate balance between heat production and heat loss. Many of the chemical reactions necessary for human survival can occur only in specific temperature ranges. The human brain has a number of ways to maintain vital temperature. When these mechanisms are overwhelmed, heat loss happens faster than heat production resulting in hypothermia.Sometimes the body’s temperature control can be altered by disease. In this case, core body temperature can decrease in almost any environment. This condition is called secondary hypothermia.

- The body loses heat in several ways.

- 55-65% is lost to the environment via radiation.

- Conduction only accounts for 2-3% in dry conditions, but this figure can increase to 50% if the victim is immersed in cold water.

- Convection accounts for 10%, while 2-9% is lost to heating inspired air.

- 20-27% is lost as a result of evaporation from the skin and lungs.

- Children cool quicker than adults because they have more surface area compared to body mass.

- The body also has a variety of methods to increase heat production. But at a certain low level, the body cannot continue heat production, and core body temperature drops quickly. From 98.6°F to 89.6°F, the body begins to shiver, blood vessels contract, and hormones generate heat.

- Shivering can double heat generation. However, this can only last a few hours. Eventually fatigue sets in, and the body exhausts its fuel stores.

- Blood vessels contract or narrow in your arms and legs, which allows warm blood to remain internal and somewhat protected from the cold temperatures to which the skin is subjected.

- Hormones and other small proteins are released in order to speed up the basal metabolic rate, essentially eating stored fuels in the hopes of producing heat as a byproduct.

- From 89.6°F to 75.2°F, shivering stops, and basic metabolism progressively slows down. At a body temperature lower than 75.2°F, almost every mechanism for heat conservation becomes inactive. Core body temperature continues to plummet. In primary hypothermia, the body is unable to generate heat fast enough to compensate for ongoing heat losses. This primarily is a disease of exposure.

- In general, in cold, dry environments, hypothermia occurs over a period of hours.

- In cold water, core temperature can drop to dangerous levels in a matter of minutes.

- The elderly, because of their impaired ability to produce and retain heat, may become hypothermic over a period of days while living in indoor, regulated conditions that other people would find comfortable.

- The homeless, alcoholics, and mentally ill are prone to hypothermia because they are unable to find adequate shelter or are unable to recognize when it is time to come in from the cold.

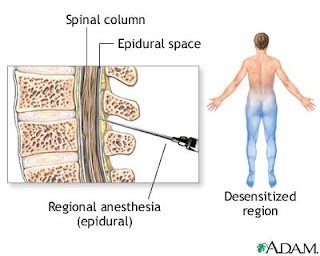

- In secondary hypothermia, something goes wrong with the body’s heat-balancing mechanisms. People with such diseases as stroke, spinal cord injury, low blood sugar, and a variety of skin disorders can become hypothermic in only mildly cool air.

Hypothermia Symptoms

Although the distinctions among mild, moderate, and severe hypothermia are not often clear, a somewhat constant sequence of events occurs as core body temperatures continue to decline.- At temperatures below 95°F (35°C), shivering is seen. Heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure increase.

- As the temperature drops further, pulse, breathing rate, and blood pressure all decrease. You may experience some clumsiness, apathy, confusion, and slurred speech.

- As core temperature drops lower than 89.9°F (32.2°C), shivering stops and oxygen consumption begins to drop. The victim may be in a stupor. The heart rhythm may become irregular.

- At temperatures below 82.4°F (28°C), reflexes are lost and cardiac output continues to fall. The risk of dangerously irregular heart rhythms increases, and brain activity is seriously slowed. The pupils are dilated, and the victim appears comatose or dead.

When to Seek Medical Care

You may treat minor cold exposure at home with blankets and home care techniques. Call a doctor to ask about danger signs that might warrant immediate transportation to a medical facility.Any person who is at risk for hypothermia and is suspected to have sustained a cold exposure should be brought to a hospital’s Emergency Department. Look for these danger signs of cold exposure:

- Intense shivering, stiffness, and numbness in the arms and legs, stumbling and clumsiness, sleepiness, confusion, and amnesia.

- The adage that "a person is not dead until warm and dead" means that victims may appear dead because of cold exposure, but many of these people have made complete recoveries when rewarmed. All such victims in this situation need rapid transport to a hospital so that resuscitation attempts may be made.

Exams and Tests

In severe cases of hypothermia, diagnosis and treatment will occur at the same time.- The doctor will take a history from either the victim, if possible, or from whoever is present. Some vital information includes the length of exposure, the circumstances of recovery, and any past medical problems that may have influenced this episode.

- Symptoms vary, so the final diagnosis depends on the core body temperature. It is never taken by mouth. The temperature may be measured rectally, by a tube placed in the esophagus, or by an instrument inserted in an ear canal. Temperature will be measured continuously.

- A long list of blood tests will be performed because hypothermia can affect almost every organ system in the body. X-rays, especially of the chest, may be ordered, and many ECGs will be done to look at the electrical activity of the heart.

Hypothermia Treatment

Self-Care at Home

- The first priority is to perform a careful check for breathing and a pulse and initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) as necessary.

- If the person is unconscious, having severe breathing difficulty, or is pulseless, call 911 for an ambulance.

- Because the victim’s heartbeat may be very weak and slow, the pulse check should ideally be continued for at least 1 minute before beginning CPR. Rough handling of these victims may cause deadly heart rhythms.

- The second priority is rewarming.

- Remove all wet clothes and move the person inside.

- The victim should be given warm fluids if he or she is able to drink, but do not give the person caffeine or alcohol.

- Cover the person’s body with blankets and aluminum-coated foils, and place the victim in a sleeping bag. Avoid actively heating the victim with outside sources of heat such as radiators or hot water baths. This may only decrease the amount of shivering and slow the rate of core temperature increase.

- Strenuous muscle exertion should be avoided.

- Some cold exposure, such as cold hands and feet, may be treated with home care techniques.

Medical Treatment

- The doctor will first assess for immediate life threats, which are primarily the lack of breathing or a pulse. If the victim is not breathing, he or she will have a tube placed to help them breathe. If the victim does not have a pulse, chest compressions will be started.

- If the person is not responding, he or she will receive a dosage of the vitamin thiamine and have a blood sugar level checked to make sure it is not low. In this way, doctors make sure these are not the reasons why the person is unconscious.

- If the heart appears on the cardiac monitor to be beating ineffectively (a condition known as ventricular fibrillation), electricity may be applied to the chest using 2 paddles in an attempt to defibrillate the heart. This procedure may be tried up to 3 times at first, and then occasionally as the person’s temperature begins to climb.

- A tube may be placed through the nose into the stomach, and a catheter inserted into the bladder to monitor urine output. An IV line will be started, and warmed fluids will be given to treat the dehydration commonly seen in people with hypothermia.

- During this time, the process of rewarming is begun. There are 3 categories of rewarming:

- Passive external rewarming (PER): This method is ideal for mild hypothermia. In order to be effective, the person must be able to generate enough heat to maintain a good rate of spontaneous rewarming. The victim is placed in a suitably warm environment and covered with insulation. Core temperature is expected to increase a few degrees per hour with this method. At a core temperature below 86°F (30°C), spontaneous shivering is lost. The person has no ability to increase his or her own temperature, and PER is ineffective.

- Active external rewarming (AER) is a controversial technique in which heat is applied to the skin. Although common sense would suggest that this would be an effective method of rewarming, it has complications. When applied to the entire body, the warmth causes the brain to dilate the blood vessels in the arms and legs from their highly narrowed state. This action can bring cold blood that was previously trapped in the arms and legs back to the core of the body and actually lower its temperature. This same blood also carries with it a large amount of toxins, including acids, which flood the core and cause a dangerous acidosis. For these reasons and others, if AER is employed, it is directed over the trunk of the body only.

- Active core rewarming (ACR) is the most effective way to rapidly increase core temperature. It avoids many of the dangers associated with external rewarming. ACR is used when the person’s heart is unstable, when body temperature is below 89.9°F (32.2°C), and when the person is rewarming too slowly or not at all or in cases of secondary hypothermia. ACR may be performed in a variety of ways.

- Airway: Warmed, humidified air is given either through the breathing tube or a closely fitted oxygen mask.

- Peritoneal dialysis: Warmed fluid is placed into the abdomen through an incision and later removed. This cycle is repeated every 20-30 minutes. The major benefit here is that the liver may be quickly rewarmed and thus able to clear the body of toxins.

- Heated irrigation: Tubes may be placed between the ribs, and heated water applied over the lungs and heart. Its effects are questionable.

- Diathermy: This is a new method in which ultrasound and low-frequency microwave radiation is employed to deliver heat to deeper tissues.

- Extracorporeal: Employing one of a variety of methods, blood is circulated from the person’s body through a warmer and then back into the bloodstream. This is the most rapid means currently available.

Follow-up

People who experience accidental hypothermia with body temperatures in the range of 95-89.9°F (35-32.2°C) and are otherwise healthy usually rewarm easily and can be safely sent home.Those whose core temperatures are below 89.9°F (32.2°C) are admitted to the hospital. Underlying medical disorders are investigated and cardiac monitoring performed.

Prevention

Prepare well before embarking on any cold weather activities.- Make sure you are conditioned physically with adequate nutrition and rest.

- Travel with a partner.

- Wear multiple layers of clothing, loosely fitted. Cover the head, wrists, neck, hands, and feet and try to remain dry.

- In an emergency, drink cold water rather than ice or snow.

- Be wary of wind and wet weather because they increase the rate of heat loss.

- Keep the homes of the elderly heated to at least 70°F (21.1°C), especially the sleeping area.

Outlook

People with accidental hypothermia in the range of 95-89.9°F (35-32.2°C) and who are otherwise healthy usually rewarm easily and can be safely sent home. Those with lower core body temperatures are usually admitted to the hospital.People with uncomplicated hypothermia do better as a group than do people with hypothermia and another associated disease. In fact, outcome depends more on the underlying disease process than the person’s initial temperature or the rewarming method employed.

Age is not always a risk factor, although elderly people tend to have more associated medical problems. People with mild to moderate hypothermia usually have a complete recovery.

People with poor outcomes usually have had cardiac arrest, a very low or no blood pressure, and the need to have breathing assisted with a tube—all before arriving at the hospital.