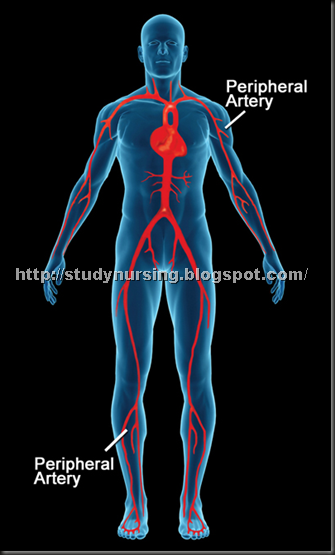

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD), also called peripheral vascular disease, is atherosclerosis of the extremities (virtually always lower) causing ischemia. Mild PAD may be asymptomatic or cause intermittent claudication; severe PAD may cause rest pain with skin atrophy, hair loss, cyanosis, ischemic ulcers, and gangrene. Diagnosis is by history, physical examination, and measurement of the ankle-brachial index. Treatment of mild PAD includes risk factor modification, exercise, antiplatelet drugs, and cilostazol or possibly pentoxifylline as needed for symptoms. Severe PAD usually requires angioplasty or surgical bypass and may require amputation. Prognosis is generally good with treatment, although mortality rate is relatively high because coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease often coexists.

Etiology

Etiology

PAD affects about 12% of people in the US; men are affected more commonly. Risk factors are the same as those for atherosclerosis: hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia (high low density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol, low high density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol), cigarette smoking (including passive smoking) or other forms of tobacco use, diabetes, and a family history of atherosclerosis. Obesity, male sex, and a high homocysteine level are also risk factors.

Symptoms and Signs

Typically, PAD causes intermittent claudication, which is a painful, aching, cramping, uncomfortable, or tired feeling in the legs that occurs during walking and is relieved by rest. Claudication usually occurs in the calves but can occur in the feet, thighs, hips, buttocks, or, rarely, arms. Claudication is a manifestation of exercise-induced reversible ischemia, similar to angina pectoris. As PAD progresses, the distance that can be walked without symptoms may decrease, and patients with severe PAD may experience pain during rest, reflecting irreversible ischemia. Rest pain is usually worse distally, is aggravated by leg elevation (often causing pain at night), and lessens when the leg is below heart level. The pain may be burning, tightening, or aching, although this finding is nonspecific. About 20% of patients with PAD are asymptomatic, sometimes because they are not active enough to trigger leg ischemia. Some patients have atypical symptoms (eg, nonspecific exercise intolerance, hip or other joint pain).

Mild PAD often causes no signs. Moderate to severe PAD commonly causes diminished or absent peripheral (popliteal, tibialis posterior, dorsalis pedis) pulses; Doppler ultrasonography can often detect blood flow when pulses cannot be palpated.

When below heart level, the foot may appear dusky red (called dependent rubor). In some patients, elevating the foot causes loss of color and worsens ischemic pain; when the foot is lowered, venous filling is prolonged (> 15 sec). Edema is usually not present unless the patient has kept the leg immobile and in a dependent position to relieve pain. Patients with chronic PAD may have thin, pale (atrophic) skin with hair thinning or loss. Distal legs and feet may feel cool. The affected leg may sweat excessively and become cyanotic, probably because of sympathetic nerve overactivity.

As ischemia worsens, ulcers may appear (typically on the toes or heel, occasionally on the leg or foot), especially after local trauma. The ulcers tend to be surrounded by black, necrotic tissue (dry gangrene). They are usually painful, but people with peripheral neuropathy due to diabetes or alcoholism may not feel them. Infection of ischemic ulcers (wet gangrene) occurs readily, producing rapidly progressive cellulitis.

The level of arterial occlusion influences location of symptoms. Aortoiliac PAD may cause buttock, thigh, or calf claudication; hip pain; and, in men, erectile dysfunction (Leriche syndrome). In femoropopliteal PAD, claudication typically occurs in the calf; pulses below the femoral artery are weak or absent. In PAD of more distal arteries, femoropopliteal pulses may be present, but foot pulses are absent.

Arterial occlusive disease occasionally affects the arms, epecially the left proximal subclavian artery, causing arm fatigue with exercise and occasionally embolization to the hands.

Diagnosis

PAD is suspected clinically but is underrecognized because many patients have atypical symptoms or are not active enough to have symptoms. Spinal stenosis may also cause leg pain during walking but can be distinguished because the pain (called pseudoclaudication) requires sitting, not just rest, for relief, and distal pulses remain intact.

Diagnosis is confirmed by noninvasive testing. First, bilateral arm and ankle systolic BP is measured; because ankle pulses may be difficult to palpate, a Doppler probe may be placed over the dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial arteries. Doppler ultrasonography is often used, because pressure gradients and pulse volume waveforms can help distinguish isolated aortoiliac PAD from femoropopliteal PAD and below-the-knee PAD.

A low (≤ 0.90) ankle-brachial index (ratio of ankle to arm systolic BP) indicates PAD, which can be classified as mild (0.71 to 0.90), moderate (0.41 to 0.70), or severe (≤ 0.40). If the index is normal (0.91 to 1.30) but suspicion of PAD remains high, the index is determined after exercise stress testing. A high index (> 1.30) may indicate noncompressible leg vessels (as occurs in Mönckeberg's arteriosclerosis with calcification of the arterial wall). If index is > 1.30 but suspicion of PAD remains high, additional tests (eg, Doppler ultrasonography, measurement of BP in the first toe using toe cuffs) are done to check for arterial stenoses or occlusions. Ischemic lesions are unlikely to heal when systolic BP is < 55 mm Hg in patients without diabetes or < 70 mm Hg in patients with diabetes; below-the-knee amputations usually heal if BP is ≥ 70 mm Hg. Peripheral arterial insufficiency can also be assessed by transcutaneous oximetry (TcO2). A TcO2 level < 40 mm Hg is predictive of poor healing, and a value < 20 mm Hg is consistent with critical limb ischemia.

Angiography provides details of the location and extent of arterial stenoses or occlusion; it is a prerequisite for surgical correction or percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA). It is not a substitute for noninvasive testing because it provides no information about the functional significance of abnormal findings. Magnetic resonance angiography and CT angiography are noninvasive tests that may eventually supplant contrast angiography.

Treatment

- Risk factor modification

- Exercise

- Antiplatelet drugs

- Pentoxifylline Some Trade Names

TRENTAL

or cilostazol Some Trade Names

PLETAL

considered for claudication - Percutaneous intervention or surgery for severe disease

Exercise—35 to 50 min of treadmill or track walking in an exercise-rest-exercise pattern 3 to 4 times/wk—is an important but underused treatment. It can increase symptom-free walking distance and improve quality of life. Mechanisms probably include increased collateral circulation, improved endothelial function with microvascular vasodilation, decreased blood viscosity, improved RBC filterability, decreased ischemia-induced inflammation, and improved O2 extraction.

Patients are advised to keep the legs below heart level. For pain relief at night, the head of the bed can be elevated about 10 to 15 cm (4 to 6 inches) to improve blood flow to the feet.

Patients are also advised to avoid cold and drugs that cause vasoconstriction (eg, pseudoephedrine Some Trade Names

AFRINOL

SUDAFED

, contained in many sinus and cold remedies).

Preventive foot care is crucial, especially for patients with diabetes. It includes daily foot inspection for injuries and lesions; treatment of calluses and corns by a podiatrist; daily washing of the feet in lukewarm water with mild soap, followed by gentle, thorough drying; and avoidance of thermal, chemical, and mechanical injury, especially that due to poorly fitting footwear. For foot ulcer management, see also Pressure Ulcers: Ulcer care.

Antiplatelet drugs may modestly lessen symptoms and improve walking distance; more importantly, these drugs modify atherogenesis and help prevent acute coronary syndromes and transient ischemic attacks (see also Coronary Artery Disease: Drugs). Options include aspirin Some Trade Names

BUFFERIN

ECOTRIN

GENACOTE

81 to 162 mg once/day, aspirin Some Trade Names

BUFFERIN

ECOTRIN

GENACOTE

25 mg plus dipyridamole Some Trade Names

PERSANTINE

200 mg po once/day, and clopidogrel Some Trade Names

PLAVIX

75 mg po once/day or ticlopidine Some Trade Names

TICLID

250 mg po bid with or without aspirin Some Trade Names

BUFFERIN

ECOTRIN

GENACOTE

. Aspirin Some Trade Names

BUFFERIN

ECOTRIN

GENACOTE

is typically used alone first, followed by addition or substitution of other drugs if PAD progresses.

For relief of claudication, pentoxifylline Some Trade Names

TRENTAL

400 mg po tid with meals or cilostazol Some Trade Names

PLETAL

100 mg po bid may be used to relieve intermittent claudication by improving blood flow and enhancing tissue oxygenation in affected areas; however, these drugs are no substitute for risk factor modification and exercise. Use of pentoxifylline Some Trade Names

TRENTAL

is controversial because evidence of its effectiveness is mixed. A trial of ≥ 2 mo may be warranted, because adverse effects are uncommon and mild. The most common adverse effects of cilostazol Some Trade Names

PLETAL

are headache and diarrhea. Cilostazol Some Trade Names

PLETAL

is contraindicated by severe heart failure.

Other drugs that may relieve claudication are being studied; they include l- arginine Some Trade Names

R-GENE

(the precursor of endothelium-dependent vasodilator), nitric oxide, vasodilator prostaglandins, and angiogenic growth factors (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], basic fibroblast growth factor [bFGF]). Gene therapy for PAD is also being studied. In patients with severe limb ischemia, long-term parenteral use of vasodilator prostaglandins may decrease pain and facilitate ulcer healing, and intramuscular gene transfer of DNA encoding VEGF may promote collateral blood vessel growth.

Percutaneous intervention: PTA with or without stent insertion is the primary nonsurgical method for dilating vascular occlusions. PTA with stent insertion may keep the artery open better than balloon compression alone, with a lower rate of reocclusion. Stents work best in large arteries with high flow (iliac and renal); they are less useful for smaller arteries and for long occlusions.

Indications for PTA are similar to those for surgery: intermittent claudication that inhibits daily activities, rest pain, and gangrene. Suitable lesions are flow-limiting, short iliac stenoses (< 3 cm) and short, single or multiple stenoses of the superficial femoropopliteal segment. Complete occlusions (up to 10 or 12 cm long) of the superficial femoral artery can be successfully dilated, but results are better for occlusions ≤ 5 cm. PTA is also useful for localized iliac stenosis proximal to a bypass of the femoropopliteal artery.

PTA is less useful for diffuse disease, long occlusions, and eccentric calcified plaques. Such lesions are particularly common in diabetes, often affecting small arteries.

Complications of PTA include thrombosis at the site of dilation, distal embolization, intimal dissection with occlusion by a flap, and complications related to heparin Some Trade Names

HEPFLUSH-10

use.

With appropriate patient selection (based on complete and adequate angiography), the initial success rate approaches 85 to 95% for iliac arteries and 50 to 70% for thigh and calf arteries. Recurrence rates are relatively high (25 to 35% at ≤ 3 yr); repeat PTA may be successful.

Surgery: Surgery is indicated for patients who can safely tolerate a major vascular procedure and whose severe symptoms do not respond to noninvasive treatments. The goal is to relieve symptoms, heal ulcers, and avoid amputation. Because many patients have underlying CAD, which places them at risk of acute coronary syndromes during surgical procedures for PAD, patients usually undergo cardiac evaluation prior to surgery.

Thromboendarterectomy (surgical removal of an occlusive lesion) is used for short, localized lesions in the aortoiliac, common femoral, or deep femoral arteries.

Revascularization (eg, femoropopliteal bypass grafting) uses synthetic or natural materials (often the saphenous or another vein) to bypass occlusive lesions. Revascularization helps prevent limb amputation and relieve claudication.

In patients who cannot undergo major vascular surgery, sympathectomy may be effective when a distal occlusion causes severe ischemic pain. Chemical sympathetic blocks are as effective as surgical sympathectomy, so the latter is rarely done.

Amputation is a procedure of last resort, indicated for uncontrolled infection, unrelenting rest pain, and progressive gangrene. Amputation should be as distal as possible, preserving the knee for optimal use with a prosthesis.

External compression therapy: External pneumatic compression of the lower limb to increase distal blood flow is an option for limb salvage in patients who have severe PAD and are not candidates for surgery. Theoretically, it controls edema and improves arterial flow, venous return, and tissue oxygenation, but data supporting its use are lacking. Pneumatic cuffs or stockings are placed on the lower leg and inflated rhythmically during diastole, systole, or part of both periods for 1 to 2 h several times/wk.

Acute Peripheral Arterial Occlusion

Peripheral arteries may be acutely occluded by a thrombus, an embolus, aortic dissection, or acute compartment syndrome.

Acute peripheral arterial occlusion may result from rupture and thrombosis of an atherosclerotic plaque, an embolus from the heart or thoracic or abdominal aorta, an aortic dissection, or acute compartment syndrome (see Fractures, Dislocations, and Sprains: Compartment Syndrome).

Symptoms and signs are sudden onset in an extremity of the 5 P's: severe pain, polar sensation (coldness), paresthesias (or anesthesias), pallor, and pulselessness. The occlusion can be roughly localized to the arterial bifurcation just distal to the last palpable pulse (eg, at the common femoral bifurcation when the femoral pulse is palpable; at the popliteal bifurcation when the popliteal pulse is palpable). Severe cases may cause loss of motor function. After 6 to 8 h, muscles may be tender when palpated.

Diagnosis is clinical. Immediate angiography is required to confirm location of the occlusion, identify collateral flow, and guide therapy.

Treatment consists of embolectomy (catheter or surgical), thrombolysis, or bypass surgery. The decision to perform surgical thromboembolectomy vs thrombolysis is based on the severity of ischemia, the extent/location of the thrombus, and the general medical condition of the patient.

A thrombolytic (fibrinolytic) drug, especially when given by regional catheter infusion, is most effective for patients with acute arterial occlusions of < 2 wk and intact motor and sensory limb function. Tissue plasminogen activator and urokinase are most commonly used. A catheter is threaded to the occluded area, and the thrombolytic drug is given at a rate appropriate for the patient's size and the extent of thrombosis. Treatment is usually continued for 4 to 24 h, depending on severity of ischemia and signs of thrombolysis (relief of symptoms and return of pulses or improved blood flow shown by Doppler ultrasonography). About 20 to 30% of patients with acute arterial occlusion require amputation within the first 30 days.

No comments:

Post a Comment